Tackling the Challenges of Adaptive Reuse

5 October 2023

In recent times, the majority of upscale construction work in the UK has favoured a new-build approach. However, at Eckersley O’Callaghan we frequently work within the heritage and refurbishment sector, so it is second nature for us to evaluate the residual capacity of an asset before considering any demolition works. With the rising recognition of adaptive re-use benefits, we’re now engaging with a broader spectrum of clients eager to explore this avenue. But what are the inherent risks?

Our approach to repurposing old buildings commences with a comprehensive fact-finding mission, spanning multiple stages of the design process. We identify and mitigate known and unknown risks, but what exactly are these risks, and how do we navigate them? Furthermore, what considerations shape our decision-making throughout this journey?

Feasibility

Although the client sets the initial brief, a structural engineering appraisal at both feasibility and concept stages informs the extent and scale of what is achieveable. Our input helps to balance and evaluate commercial viability across several options from light touch to major interventions whilst the overall ambition of the project should be agreed holistically, taking views from the full design team.

Our work typically begins with a desk study obtaining historic records, geological information, planning records, archive searches and a visual survey. Proving the suitability of the existing building and the associated extensive refurbishments can be challenging, especially when accurate records are lacking. Once the building age is determined, through planning department portals, Heritage Consultants or other archive searches, we can explore its primary structural materials and any likely period defects it may comprise. If access permits, these potential risks are further explored by scoping of trial openings and investigations. This is where the contractor exposes the structure so that we as the engineer can gain a clear picture of the primary structure.

Sustainability

Next, we consider the scale of new proposals in relation to the original asset. One of the IStructE principle guidelines for sustainability is to simply ‘build less’. We strongly believe these concepts, which we apply to every building are (in this order): Build nothing – Build less – Build clever – Build efficient – Minimise waste – Build low carbon. Some client’s briefs can be achieved without unecessry material expenditure and structural intervention, but if not, how can we make structural modifications required with minimal environmental impact?Preserving the existing structure, while sensitively extending and upgrading it, can deliver high-quality space without the carbon and monetary cost of providing a new primary frame. Where it is anticipated that superstructure strengthening works are required, we aim to use spatially and materially efficient techniques, while maintaining architectural layouts and headroom. An example of this is our LSBU London Road project, where we used Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) to strengthen the existing 1970’s concrete frame, a project recognised for its minimal intervention with high impact.

Design Loads

Historical design loads, as documented in guidance materials, were typically higher than today’s allowances for similar uses. This often provides room to justify an increase in loading for an older building, provided assumptions about the existing load are validated, and the structure is in good condition. Regardless, it’s crucial to exercise caution when assuming existing design loads and conduct further design checks on existing structural systems. Even if we establish that the original design loading is equivalent to the new usage, for longer span structures we also need to check for vibration – these weren’t really covered in the guidance until recent times so when re-purposing an old building, we must consider re-assessing it against modern requirements.

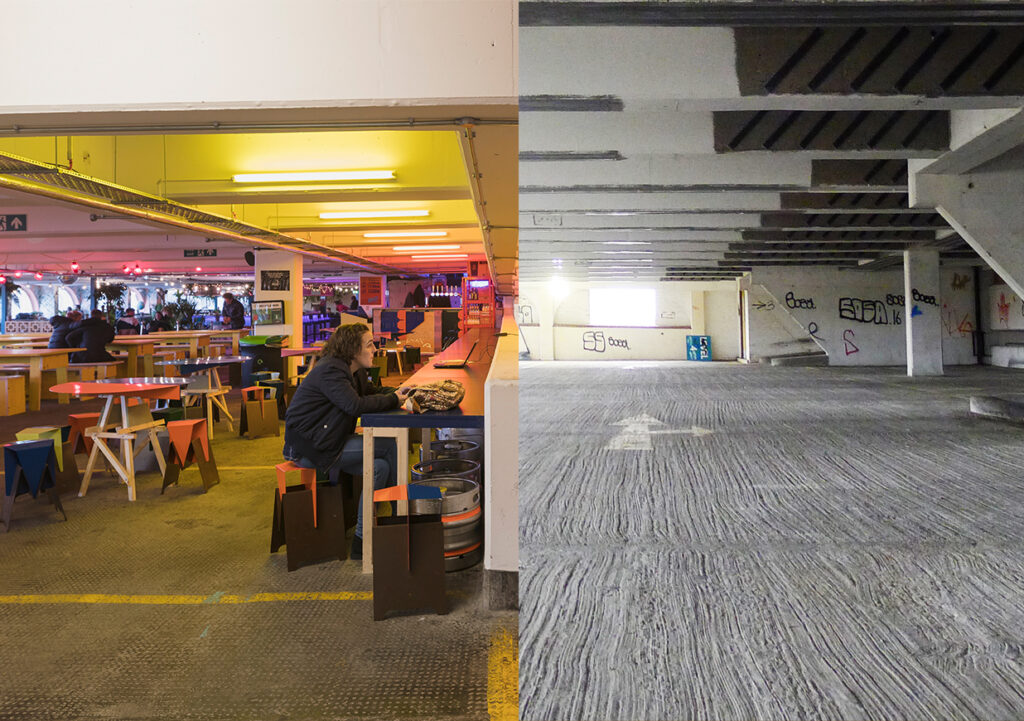

Change of Use

Adaptive reuse projects often involve changing the use of a building, which may adversely raise or conveniently lower the design loading. A close look at the original record drawings, an assessment of the historic ownership, and retrospective check on the steelwork capacity can be fruitful. Our project at Peckham Levels involved converting a multistorey car park into a space encompassing everything from bars to restaurants. The client was surprised to hear that following a detailed assessment of the building, car park loading was lower than the proposed adaptation. A system of carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP) plates were bonded to the existing structure, increasing the capacity of the building without the need to introduce additional columns into the open plan of the current carpark.

Disproportionate Collapse

For vertical extensions, designers must ensure the new structure can be implemented without increased risk with respect to ‘disproportionate collapse’; a part of the regulations introduced following the Ronan Point failure in 1968. These regulations state that we must design to have enough robustness and redundancy such that failure of a single element does not lead to catastrophic collapse. This was a late 1960’s addition to building regulations, therefore all buildings designed and built before this, will need to be re-appraised and are classified into categories of risk based on use and height.

Certain structures can also be more difficult to justify from a collapse perspective. Masonry wall panels for example, are sensitive to the removal of wall panels in an accidental scenario and often need to be strengthened or a more robust approach taken to mitigate the failure mode of the masonry. A strongfloor approach to vertical extension is generally accepted; a technique which involves the installation of a steel grillage at the current roof level. This method is used to ensure that the newly installed floors above current roof level are capable of bridging over potentially large gaps in the historic structure below, should they be damaged or destroyed in the accidental case.

Even without increasing the internal area, upgrading the existing structure for robustness is advisable if it doesn’t comply with current regulations and is best practice. These upgrades are often cost-effective with minimal architectural impact. Our project on New Bridge Street, is an example of where the existing structure didn’t conform to the current robustness guidance and as such we proposed an efficient upgrade the existing member connections to mitigate the risk of a potential disproportionate failure scenario.

Fire Periods

Another critical consideration is the original design fire periods for the existing structure, which demands diligent attention, particularly post Grenfell and in light of upcoming regulations. Historic buildings may have undergone many previous alterations such as:

- their masonry walls could be pocketed and contain timber batons

- a reinforced concrete frame might not have enough cover to the reinforcement, which requires extensive cover surveys to validate

- a steel frame may not have any coating protection or inadequate boarding to protect the primary horizontal and vertical elements

- The clinker floor maybe have delaminated from the steel joists

Consideration of these items must always be illustrated in the cost plan and on the design risk register as failure to address these items can have more severe consequences with respect to program and cost. Designers and contractors are becoming increasingly aware of these risks and are building them into their assessment.

The challenges of adaptive re-use, in the context of structural engineering and particularly heritage refurbishment, are complex but navigable with careful consideration and expertise. At Eckersley O’Callaghan, we have got a wealth of experience and know-how in resolving the challenges mentioned above. We continuously improve our knowledge that aids us develop a carefully calibrated approach to each adaptive reuse project. This involves not just our structural engineering expertise, but also coordination with other disciplines and early-stage evaluations of commercial and technical viability of proposals. Embracing adaptive re-use offers a sustainable approach to construction, aligning with principles of minimising environmental impact and preserving existing and historical assets. However, it requires meticulous planning, risk assessment, and a holistic view that transcends the binary choice of demolition versus new-build.

Eckersley O’Callaghan credit: David Blackburn

Adaptive Reuse Part 1

Adaptive Reuse Part 3